mercredi, 22 octobre 2014

Etymologie - Romantique #3

Crédits photographiques Elie Mehdi

Extrait de Romancing the Market, Brown, Doherty & Clarke, 1998, Routledge :

p.2

Like many aesthetic movements, of course, romanticism only really makes sense in terms of what it is not. And the 'not' that romanticism is usually compared to is neoclassicism (allbeit the case for 'realism' is probably sttonger - see Travers 1998).

As the term implies, neoclassicism essentially involved the excavation, establishment, elaboration and enactment of aesthetic ideas derived from ancient Greek and Roman arbiters like Aristotle, Horace, Quintilian and Longinus (Abrams 1993; Barzun 1962). These authorities were assumed to have attained unequalled excellence in their respective spheres of endeavour and thus their writings were regarded as models to which all great art should aspire. Neoclassicism, then, was characterised by conformity, traditionalism, distrust of radical

p.3

innovation and an overwhelming emphasis upon the tried and tested. Its leading eighteenth-century exponents, such as Swift, Dryden, Pope and Goldsmith, stove for elegance, grace, decorum, propriety and adherence to, or refinement of, the 'rules' of the relevant genre. Innovation, admittedly, was by no means depreciated but the primary challenge was to display wit, ease, suavity, sophistication, skill and polish within existing, highly restricted conventions (in drama, the three unities of time, place and action, the closed couplet in poetry, etc.).

As Furst (1969: 15) observes, the authoritarianism of the neoclassical period largely stemmed from an unqualified belief in the powers of the mind, the intellect and, above all, reason. The scientific achievements of the Enlightenment fostered an assumption that all things were knowable and that this knowledge was attainable by means of rational investigation. Just as Newton had shown this to be the case in the physical world, so too the milieux of morals, politics, ethics and art could be systematically examined and their universal 'truths' uncovered, extracted and disseminated.

The adepts of neoclassicism thus attempted to establish the 'laws' of aesthetics, which if properly observed and carefully followed would result in a 'correct' composition, be it musical, literary, dramatic or whatever. 'The Rtist, like the scientist, was expected to operate by calculation, judgement and reason, for... the making of a book was considered a task like the making of a clock' (Furst 1969: 16).

The romantics, by contrast, championed innovation, creativity, iconoclasm, individuality and radical experimentation over traditionalism, refinement, rectitude and the seemly veneration of extant materials, forms, styles or genres (Butler 1981; Cranston 1994). They espoused spontaneity, informality, exuberance, elementalism, naturalism and aboriginal rusticity - as, for instance, in their use of vernacular language, their enthusiasm for 'lowly', 'impolite' or 'common' subjects, and, not least, their unqualified love of nature, landscape and the sheer élan vital of exitence. Conspicuously non-rational perspectives predicated upon visionary, mystical, supernatural, spiritual and otherworldly experiences came to prominence in the romantic period, as did a veritable catalogue of halt, lame and lonely wanderers, noble savages, innocent children, restless phantoms, pastoral panoramas, verdant vistas, sylvan glades, faery grottoes, crumbling ruins, gnarled oaks and, lest you think we've forgotten, golden daffodils. ALthough described with remarkable accuracy, compassion and power, it must be stressed that such 'external' phenomena primarily served to stimulate the inner feelings/reflections/emotions/introspections of the poet, author or creative artist.

Much of romanticism's legacy therefore comprises meditations or reveries on the creator's inner Self, though, as these people were often social misfits, nonconformists or malcontents, it is dominated by melancholic, anxiety-stricken, self-pitying expressions of the inner emotional turmoil of imaginative outsiders. Imagination, in short, coupled with an apocalyptic sense of out-with-the-old-and-in-with-the-new, was the cynosure of the romantics (Barzun 1944; Bowra 1961; Day 1996; Shaffer 1995). Romanticism is nothing less than an 'apocalypse of the imagination' (Bloom 1970a: 19).

p.10

[...] the romantic hero [...] is charismatic, dynamic, exciting, risk-taking, adventurous, outrageous, restless, roguish, swashbuckling, sexy. A bit Byronic perhaps, a tad Don Juanish and Manfred is manifestly its middle name [...]. Like Goethe's Werther, Chateaubriand's René and Musset's Octave, marketing constantly oscillates between profound, almost suicidal melancholy (e.g. the contemporary 'crisis' literature and the perennial complaint that no one takes the discipline seriously) and rampant, well-nigh certifiable megalomania (the broadening debate, periodic paroxysm of 'rediscovery', etc.). The romantic hero may be 'a multiple persona which drew upon images of the aristocrat, the dandy, the womaniser, the sociol and political outcast, and the rebel' (Travers 1998: 18), yet he is no less prone to 'lose a sense of perspective through constant self-observation, self-analysis and self-pity, so that he sinks deeper and deeper into the quagmire of his egocentricity' (Furst 1969: 98). Do they mean us ?

_ _ _

Contributors are Eric J. Arnould, Russel W. Belk, Stephen Brown, Bill Clarke, Anne Marie Doherty, Benoît Heilbrunn, Morris B. Holbrook, Christian Jantzen, Pauline Maclaran, Andrew McAuley, Per Ostergaard, Cele Otnes, Paul Power, Linda L. Price, Barbara B. Stern, Lorna Stevens, Craig J. Thompson, Robin Wensley

_ _ _

Abrams, M.H. (1993), A Glossary of Literary Terms, sixth edition, Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace.

Barzun, J. (1944), Romanticism and the Modern Ego, Boston: Little Brown.

Barzun, J. (1962), Classic, Romantic and Modern, London: William Pickering.

Bloom, H. (1970a), 'The internalization of quest romance', in H. Bloom, The Ringers in the Tower: Studies in Romantic Tradition, Chicago: Univeristy of Chicago Press, 12-35.

Bowra, M. (1961), The Romantic Imagination, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, M. (1981), Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries: English Literature and its Background 1760-1830, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cranston, M. (1994), The Romantic Movement, Oxford: Blackwell.

Day, A. (1996), Romanticism, London: Routledge.

Furst, L.R. (1969), Romanticism in Perspective: A Comparative Study of Aspects of the Romantic Povements in England, France and Germany, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Shaffer, E. (1995), 'Secular apocalypse: prophets and apocalyptics at the end of the eighteenth century', in M. Bull (ed.), Apocalypse Theory and the Ends of the World, Oxford: Blackwell, 137-58.

Travers, M. (1998), An Introduction to Modern European Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

_ _ _

Romancing the Market

Stephen Brown, Anne Marie Doherty, Bill Clarke

1998

Ed. Routledge

312 pages

http://www.amazon.fr/Romancing-Market-Stephen-Brown/dp/04...

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Les mots français, Photographie, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

mardi, 21 octobre 2014

Etymologie - Romantique #2

Crédits photographiques Elie Mehdi

Extrait de Romancing the Market, Brown, Doherty & Clarke, 1998, Routledge :

p.1

Two hundred years ago, a brace of young poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scandalised polite society when they published the first edition of their poetic manifesto, Lyrical Ballads (Brett and Jones 1991). Inspired, in part, by the emancipatory euphoria that accompanied the unfurling of the French Revolution, and containing such never-to-be-forgotten (once-learnt-by-rote) classics as Tintern Abbey and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Lyrical Ballads ushered in a whole new era of Western culture, commonly known as romanticism or the romantic movement (Day 1996).

True, Wordsworth and Coleridge didn't actually employ the term 'romantic' (Furst 1971). The word and its cognates, what is more, were in widespread use prior to 1798 (Sanders, 1996). Indeed, the originality of Lyrical Ballads has also been called into question, as has the extent of the controversy surrounding its publication (Ashton 1996).Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that, thankgs in no small part to Wordsworth and Coleridge, the dog days of the eighteenth century witnessed a revolution in aesthetics, in sensibility, in thought. Not only did this represent, as Berlin (1991: 209) rightly records, 'the largest shift in European consciousness since the Reformation', but romanticism is still with us in the shape of our own great '-ism', our -ism in excelsis, the nulli secundus of -isms, postmodernism (Elam 1992; Livingston 1997 ; Readings and Schaber 1993).

p.2

The basic problem with -isms, of cours, is isn't (Brown 1995). That is to say, when it comes to -isms there isn't a single, satisfactory, all-encompassing, universally agreed definition, or even agreement on the fact that there isn't a single, satisfactory, all-encompassing, universally agreed definition of the -ism in question.

Whether it be realism, relativism, conservatism, liberalism, idealism, empiricism, communism, capitalism, fscism, feminism, gnosticism, aestheticism, asceticism, athleticism, mysticism, mesmerism, masochism, modernism, marxism, malapropism or any othe '-ism' that those mad for macaronicism, liable to lexiphanicism or smitten by sesquipedalianism are inclined to conjugate, the only thing that everyone knows for certain is that there is no certainty about the thing everyone 'knows". The ism isn't.

The same is true for romanticism, a subject which has been subject to all manner of competing definitions ranging from Rousseau's 'return to nature", though Pater's 'the addition of strangeness to beauty', to Phelps's 'sentimental melancholy' (see Furst 1971). How, for that matter, can we possibly forget Goethe's contention that 'romanticism is disease' (young Werther has a lot to be sorrowful for), Ker's suggestion that it represents 'the fairy way of writing' (not in this neck of the woods, buster !), and Fairchild's cryptic confabulation that romanticism comprises 'a desire to find the infinite within the finite, to effect a synthesis of the real and the unreal, the expression in art of what in theology would be called pantheistic enthusiasm' (keep taking the tables, sunshine, or the laudanum at least) ?

Aptly described as 'baffingly vague and used in an appallingly large number of different ways in different contexts' (Gray 1992: 251), romanticism is degined in The Oxford Companion to English Literature as :

A literary movement, and profound shift in sensibility, which took place in Britain and throughout Europe... Intellectually it marked a violent reaction to the Enlightenment. Politically it was inspired by the revolutions in America and France... Emotionnaly it expressed an extreme assertion of the self and the value of individual experience together with the sense of the infinite and transcendental... The stylistic keynote of romanticism is intensity, and its watchword is 'imagination".

(Drabble 1995: 853)

_ _ _

Contributors are Eric J. Arnould, Russel W. Belk, Stephen Brown, Bill Clarke, Anne Marie Doherty, Benoît Heilbrunn, Morris B. Holbrook, Christian Jantzen, Pauline Maclaran, Andrew McAuley, Per Ostergaard, Cele Otnes, Paul Power, Linda L. Price, Barbara B. Stern, Lorna Stevens, Craig J. Thompson, Robin Wensley

_ _ _

Ashton, R. (1996), The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Oxford: Blackwell.

Berlin, I. (1991), 'The apotheosis of the romantic will: the revolt against the myth of an ideal world', in I. Berlin (ed.), The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas, London: Collins, 207-37.

Brett, R.L. and Jones, A.R. (1991), 'Introduction', in W. Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, London: Routledge, ixi-liv.

Brown, S. (1995), Postmoderne Marketing, London: Routledge.

Day, A. (1996), Romanticism, London: Routledge.

Drabble, M. (ed.) (1995), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elam, D. (1992), Romancing the Postmodern, London: Routeledge.

Furst, L.R. (1971), Romanticism, London : Methuen.

Gray, M. (1992), A Dictionary of Literary Terms, Harlow: Longman.

Livingston, I. (1997), Arrow of Chaos : Romanticism and Postmodernity, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Readings, B. and Schaber, B. (eds) (1993), Postmodernism Acreoss the Ages: Essays for a Postmodernity That Wasn't Born Yesterday, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Sanders, A. (1996), A Short Oxford History of English Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_ _ _

Romancing the Market

Stephen Brown, Anne Marie Doherty, Bill Clarke

1998

Ed. Routledge

312 pages

http://www.amazon.fr/Romancing-Market-Stephen-Brown/dp/04...

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Les mots français, Photographie, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

lundi, 20 octobre 2014

Etymologie - Romantique #1

Crédits photographiques Jana Hobeika

Extrait de Romancing the Market, Brown, Doherty & Clarke, 1998, Routledge :

Pré-intro

Two hundred years ago the romantic movement precipitated a revolution in aesthetics, sensibility and thought. The neoclassical ethos of order, rectitude and rationality was replaced by an emphasis on creativity, innovation, individuality, spontaneity and imagination.

Marketing, as an academic discipline, is dominated by neoclassical ideals of dispassionate science, 'truth' and objectivity. The international contributors* to this volume argue for a neo-romantic approach to Marketing scholarship which will invigorate, infuriate and illuminate the discipline. [...]

By way of a prelude p.xviii

In our fragmented, de-centred, hyper-real, ever-accelerating fin de siècle marketing milieu, where mechanistic, technocratic, pseudo-scientific models of analysis, planning, implementation and control no longer seem to 'work', a radically different approach to marketing understanding is urgently required.

For many contemporary commentators, poets, novelists, creative artists and their copious late twentieth-century avatars - journalists, movie makers, television producers, stand-up comedians, etc. - can provide insights into the post-human condition that are as good as if not better than those derived from more established scholarly sources. [...]

p.xix

What's more, the notion that creative writers and artists are blessed with what Ernst Bloch terms 'anticipatory illumination', an ability to articulate the as-yet-inarticulate, to make the inchoate cohere, has been around for a very long time. [...]

Romanticism has been defined in a host of ways, but a central component is the enormous emphasis placed upon the imagination, the inspiration, the inner light of the creative writer and artist. The work of the romantics didn't so much passively reflect as actively illuminate that to which it referred. Illumination, as Abrams rightly observes, is the apotheosis of romanticism.

Illumination, tu be sure, is a wonderful word. Apart from its connection to the romantic movement, it carries connotations of Arthur Rimbaud, secret societies, stained-glass windows, medieval scriptoria, illuminated manuscripts, Welter Benjamin and, Heaven help us, the recent comeback album by 1970s' rock band, Wishbone Ash. For many Britons, moreover, illuminations is evocative of Blackpool, that vulgarian of urbanism, that civitas of the carnavalesque, that municipality of marketing. Blackpool, in many ways, is a perfect metaphor for marketing scholarship. It caome to prominence approximately 100 years ago ; it reached its peak in the late 1950s-early 1960s ; and, according to some authorityies, it is in terminal decline despite increasingly desperate attempts to add to its attraction ('roll up, roll up, Relationship Marketing, the biggest white elephant of the world'). Marketing practice, what is more, has long been characterised by the irreverent, bawdy, candy-flossed, end-of-the-pied, saucy picture postcard, dirty weekend spirit that is embodied, indeed epitomised, by Blackpool ('buy one get one free", "I can't believe it's not butter', 'FCUK' and, naturally, 'Beaver Espana').

p.xx

[...] ... about the romanticism of marketing on St Valentine's Day, of all days. Not only does St Valentine's Day epitomise the commercialisation of love - marketing the romance, so to speak - but the festival commemorates an early Christian priest, who was beheaded in 269CE for conducting the marriage ceremonies of covert lovers, though some say it was because he cured and converted the blind daughter of a Roman official. Yet others maintain that it was Valentine's voluminous outpouring of inflammatory letters and pamphlets during his incarceration - hence the tradition of sending cards - that precipitated the death penalty.

Be that as it may, this combination of decapitation, deception and discourse, with just a frisson of Levittite astigmatisme, cannot fail to send shivers down the spine of late twentieth-century marketing scholars. [...]

_ _ _

* Contributors are Eric J. Arnould, Russel W. Belk, Stephen Brown, Bill Clarke, Anne Marie Doherty, Benoît Heilbrunn, Morris B. Holbrook, Christian Jantzen, Pauline Maclaran, Andrew McAuley, Per Ostergaard, Cele Otnes, Paul Power, Linda L. Price, Barbara B. Stern, Lorna Stevens, Craig J. Thompson, Robin Wensley

** Marxist German philosopher, 1885-1977 > http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Bloch

_ _ _

Romancing the Market

Stephen Brown, Anne Marie Doherty, Bill Clarke

1998

Ed. Routledge

312 pages

http://www.amazon.fr/Romancing-Market-Stephen-Brown/dp/04...

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Les mots français, Photographie, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : romantique, romantisme, valentin, saint valentin, blackpool, romanticism

vendredi, 12 septembre 2014

Pendant ce temps, y'en a qui font du shopping

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Peinture, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, shopping

jeudi, 11 septembre 2014

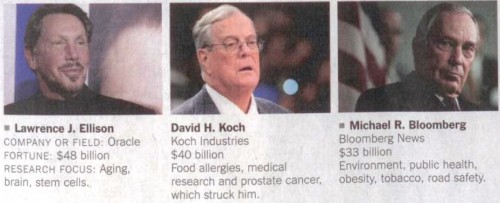

Considérations sur l'argent - Money Science

This is science money

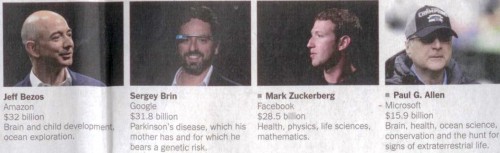

"Face of science is reshaped by billionaires", William J. Broad, The New York Times supplément au Figaro et vous, supplément au Figaro, 25 mars 2014 :

As public spending cuts result in labs shut down, scientists laid off and projects shelved, a profound change is taking place in the way science is paid for and practiced.

"For better or worse," said Steven A. Edwards of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, "the practice of science in the 21st century is becoming shaped less by national priorities or by peer-review groups and more by the particular preferences of individuals with huge amounts of money."

Science is increasingly becoming a private enterprise. From Silicon Valley to Wall Street, science philanthropy is hot, as many tycoons seek to reinvent themselves as patrons of social progress through science research.

More than a decade ago, Paul G. Allen, a founder of Microsoft, set up a brain science institute to which he donated $500 million. Fred Kavli, a technology and real estate billionaire, then established three brain institutes. It was this richely financed private research that gave birth to what President Obama last April called "the next great American project" - a $100 million initiative to probe the mysteries of the human brain.

The very rich have also mounted a private war on disease, with new protocols that beak down walls between academia and industry to turn basic discoveries into effective tratments. They are financing hunts for dinosaur bones and giant sea creatures. They are even beginning to challenge Washington in big science, with innovative ships, undersea craft and giant telescopes - as well as the first private mission to deep space.

These are people like Michael R. Bloomberg, the former New York mayor (and founder of the media company that bears his name), James Simons (hedge funds) and David H. Koch (oil and chemicals), among hundreds of wealthy donors. Especially prominent, though, are some of the biggest names in the tech world, among them Bill Gates (Microsoft), Eric E. Schmidt (Google) and Lawrence J. Ellison (Oracle).

They are donors who are impatient with the deliberate, and often politicized, pace of public science, they say, and willing to take risks that government cannot or simply will not consider.

Yet that personal setting of priorities is precisely what troubles some in the science establishment. Many of the patrons, they say, are ignoring basic research for a jumble of popular, feel-good fields like environmental studies, space exploration and, as in the case of Russia's Dimitry Itskov, a former media magnate, lifelike avatars.

Nature, a family of leading science journals, has warned that while "we applaud and fully support the injection of more private money into science, the financing could also "skew research" toward fields more trendy than central."

"Physics isn't sexy," William H. Press, a White House science adviser, said. "But everybody looks at the sky."

[...]

07:00 Publié dans Politique & co, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

mardi, 09 septembre 2014

Considérations sur le roman II - quand l'écriture frontale engagée n'est pas envisageable

*

* *

Le roman, quand l'écriture frontale engagée n'est pas envisageable

Le roman, pour donner un visage et une voix aux geôliers, aux tortionnaires, aux assassins

Le roman, pour désensorceler l'histoire à travers la littérature

Pour explorer les espaces de silences à travers une parabole dantesque

* *

*

"Désensorceler l'histoire", Thierry Clermont - tclermont@lefigaro.fr -, Le Figaro, fascicule Le Figaro et vous, jeudi 12 juin 2014

Etoile montante de la jeune génération, ayant grandi pendant la période de transition qui a succédé à l'effondrement de l'URSS? Sergueï Lebedev a publié, à trente et un ans, un premier roman magistral : La limite de l'oubli. Son incipit donne le ton, nous laisse deviner le souffle poétique qui va traverser cette fresque septentrionale : "Je me trouve à l’extrémité de l'Europe. Ici, on voit, à nu dans chaque falaise, l'os jaune de la pierre et une terre ocre ou flamboyante semblable à de la chair."

Lebedev nous dévoile une Atlantide imaginaire qui s'étend sur 300 pages, une quête et une enquête à travers le grand Nord sibérien, au-delà du cercle polaire, sur les traces laissées par les camps, sur l'engloutissement de l'archipel du goulag.

Le narrateur, ayant survécu, enfant, à la morsure d'un chien grâce à une transfusion sanguine, cherche à connaître l'identité et la vie de celui dont le sang coule désormais dans ses veines. S'ensuit une errance à travers la taïga silencieuse, les marécages sibériens, les paysages de désolation et d'abandon à la Tarkovski : baraquements désossés, anciens ateliers, neige immobile, cimetières fantômes, entre ciel et bouleaux... Au fil des pages, on comprend qu'en Russie, l'éviction de la mémoire s'est réalisée dans la géographie, dans les cartes.

Lebedev ne témoigne pas sur l'univers concentrationnaire en soi mais s'interroge sur la façon dont celui-ci s'est diffusé dans la société russe, à travers la mémoire, l'oublie et le secret. En traquant ces empreintes émotionnelles, l'auteur, petit-fils d'un officier ayant combattu à Stalingrad, a réussi un coup de force qui lui permet de regarder le présent au miroir d'un passé tragique. Un miroir brisé, qui ici ou là, par la puissance des descriptions d'une belle force onirique, apparaît comme un vitrail éclaté. Dans son cheminement vers la mémoire, avec pour témoins objectifs les lacs, les forêts et la toundra, l'écrivain est parvenu à trouver un langage pour dire cette mémoire en péril, ce hiatus entre savoir et non-savoir : La limite de l'oubli peut se lire comme le représentation géographique de ce hiatus.

Il y a quelques jours, Lebedev était de passage à Paris où il déclarait : "Mon but est de désensorceler l'histoire de la Russie à travers la littérature. Fragiles historiquement, nous avons à peine émerge comme génération. Nous sommes une génération dispersée, privée de solidarité, un groupe qui n'est pas constitué. Nous vivons comme si bourreaux et victimes n'avaient jamais eu d'enfants. Nous souffrons de ce chaînon manquant. Et cet héritage vit en nous tous, à travers nos peurs et nos angoisses. Pour ma part, je ne me sens pas particulièrement proche des autres jeunes écrivains russes. La littérature d'aujourd'hui est une sorte de champ de mines où chacun d'entre nous sait pertinemment où les mines sont cachées... où chacun est surtout intéressé par lui-même. Dans mon roman j'ai voulu redonner un visage, une voix, aux geôliers, aux tortionnaires, aux assassins. Ces acteurs n'ont jamais pris la parole... J'ai exploré ces espaces de silence à travers une parabole dantesque.

Journaliste à la revue Pervoïe Sentiabria (Premier septembre), Lebedev, qui revendique l'influence de Buzzati, Melville, Proust proust et Brodsky, vient d'achever son second roman, L'Année de la comète, à paraître chez Verdier en 2015 [...]

La limite de l'oubli

Sergueï Lebedev

2014

Traduit par Luba Jurgenson

Verdier

316 pages

www.amazon.fr/limite-loubli-Sergueï-Lebedev/dp/286432749X/

07:00 Publié dans Ecrits, littérature contemporaine, Réflexions, philosophie, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : verdier, la limite de l'oubli, sergueï lebedev, auteur russe, ecrivain russe, roman russe

lundi, 08 septembre 2014

Considérations sur le roman I

*

* *

Le roman, quand l'écriture frontale engagée n'est pas envisageable

Le roman, pour donner la parole aux miséreux comme aux arrivistes,

aux humiliés, aux offensés, proscrits et exclus

* *

*

"[...] Les jeunes auteurs critiquent la décadence morale de leur pays", entretien de Fanny Mossière (éditrice) par Thierry Clermont - tclermont@lefigaro.fr -, Le Figaro, fascicule Le Figaro et vous, jeudi 12 juin 2014

Le Figaro : Qu'est-ce qui caractérise la jeune littérature russe ?

Fanny Mossière : En Russie, les revues littéraires (Znamia, Novy Mir, Oktyabr...) sont très actives. C'est d'abord par ce biais que le public découvre les nouvelles voix de la littérature. Bien souvent, les romans y sont publiés en plusieurs fois, avant de paraître en volume : c'est le cas de Mikhaïl Chichkine, Pismovnik (traduit par Deux heures moins dix), best-seller en Russie. Zakhar Prilepine, Roman Sentchine, Oleg Pavlov ont d'abord été publié en revue ; celles-ci font office de défricheurs pour les maisons d'édition. Les écrivains des années 1990-2000 s'intéressent au contexte social et à la vie quotidienne ; la tendance est réaliste, voire hyperréaliste. Le discours est social et politique ; aujourd'hui comme tout au long de l'histoire de la Russie, l'écrivain se doit d'être engagé.

Dmitri Bykov, auteur de satires politiques, publie des chroniques dans la presse, s'exprime à la radio et à la télévision. Prilepine est populaire précisément en raison, de son engagement politique ; ses romans (pour la plupart traduits en français) mettent souvent en scène des activistes, généralement d'extrême gauche. Les jeunes écrivains décrivent la misère sociale, le chaos qui a suivi l'effondrement de l'URSS, la corruption, l'arrivisme et la perte de repères. Ils mettent en regard le passé soviétique avec la société actuelle. Beaucoup situent leurs textes dans les années 1990, marquées par la corruption et la désorganisation totale.

Parmi eux, Roman Sentchine est un cas à part. Qu'apporte-t-il de nouveau ?

Souvent cité par les écrivains de sa génération comme un modèle, Sentchine est l'un des représentants de ce "nouveau réalisme" : il décrit avec une précision clinique les difficultés du quotidien et les conséquences de la bataille permanente que livrent les Russes pour échapper à la misère. Dans Les Eltychev, l'écrivain dépeint la déchéance d'une famille sibérienne, contrainte de quitter sa petite ville pour un village sinistré. Autre illustration : dans Informatsia, Sentchine décrit l'arrivisme de la nouvelle classe moyenne moscovite ; les personnages, en proie à la solitude et au vide, font preuve de la même dégradation morale que leurs alter ego de la province.

Quelles sont leurs principales influences ?Les écrivains de la nouvelle génération traitent également des grands thèmes de la littérature universelle, comme l'amour, la mort, la relation à Dieu et à la nature. En cela, ils se réclament de la littérature russe des XIXe et XXe siècles et revendiquent l'influence de Tolstoï, Dostoëvski, Bounine, lauréat du Nobel en 1933. Pour d'autres, Edouard Limonov est la référence absolue. Oleg Pavlov, qui a publié son premier roman en 1994, à 24 ans (Conte militaire, publié en français dans la trilogie Récits des derniers jours en 2012), plonge le lecteur au cœur de l'armée, aux confins d'un empire dévasté. Dans Le Banquet du neuvième jour, Pavlov use de son talent de portraitiste et de son humour noir pour raconter l'odyssée délirante d'un détachement qui rapatrie le cadavre d'un soldat. Ses descriptions des camps de l'armée évoquent le goulag, mais aussi le moment absurde et tragique du déclin de l'empire. Fidèle au thème des humiliés et des offensés, Pavlov reflète les aspects obscurs de l'existence, le monde des proscrits et des exclus, de l'histoire cruelle, presque fantastique, de la Russie.

07:00 Publié dans Ecrits, littérature contemporaine, Réflexions, philosophie, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)