dimanche, 29 mars 2015

Strauss - PEPA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0oqRBmuRM2A

Dans la fratrie Strauss, j'ai toujours eu une prédilection pour Josef, le cadet, - davantage que pour Johann, l'aîné, ou Eduard, le benjamin... Johann lui-même reconnaissait volontiers : "C'est, de nous trois, Josef qui est le plus sensible, le plus artiste, et le plus doué, comme musicien... heureusement, c'est moi qui reste le plus populaire"... émoticône wink

Il serait malveillant d'ajouter que la mort précoce de Josef laissa définitivement la royauté de la valse viennoise à son aîné, - et que celui-ci en fut "inconsolablement" soulagé... émoticône devil

Cela dit, c'est Josef, ce jouisseur mélancolique, qui "inventa" la recette qui fit la fortune de Johann, - et l'aida, par ses trouvailles, à hausser la valse à un niveau musical qui outrepassait le simple accompagnement à trois temps, strictement cadencé pour les frottages de parquet ciré du bout de l'escarpin verni...

J'ignore si c'est, - autour de ses opus 100-110, dans les années 1860 -, à cause de la certitude qu'il avait de mourir jeune, des suites fatales d'une leucémie endémique, compliquée de syphilis, que Josef Strauss se mit à avoir ce qu'on peut bien appeler du génie, - et une touche personnelle de composition qui, d'un coup, révolutionna la musique de danse...

C'est lui, en tout cas, qui agrémenta la valse d'un climat et d'une forme de véritable "poème symphonique", voire "psychologique"... en y adjoignant une introduction "d'atmosphère", de plus en plus longue et développée, - et en y osant, dans les variations et le développement, des modulations et des raffinements harmoniques et orchestraux dignes de la salle de concert...

Ce n'est pas un hasard, si "l'autre Strauss" de Bavière, - Richard - quand il voulut honorer le "Wiener Geist", à travers les diverses citations et subtiles mises en abymes de son "Rosenkavalier" emprunta (pour évoquer la Vienne de Mozart et de Marie-Thérèse...! émoticône grin ) le thème, non d'une valse de Johann... mais, de l'une des plus belles et troublantes qu'ait composées Josef : "Dynamiden"... dont le "programme" est, d'ailleurs, presque une anticipation, avant la lettre, de ce que pépé Siegmund couchera sur le divan, et aura de plus cher... puisqu'il s'agit d'y évoquer ces "puissances secrètes et mystérieuses des sens et de l'esprit qui attirent les êtres, malgré eux, l'un à l'autre, comme un fluide irrésistible d'électricité"...

Le désir, quoi... et, le plaisir, mesdames...!

Pierre-Emmanuel Prouvost d'Agostino

15 mars 2015

> Pour un quizz : http://www.quizz.biz/quizz-319327.html

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Musique, Peinture, Sculpture | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : strauss, valse

lundi, 22 décembre 2014

La Nuit - Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

Opéra Garnier

O nuit, viens apporter à la terre

Le calme enchantement de ton mystère

L'ombre qui t'escorte est si douce

Si doux est le concert de tes voix chantant l'espérance

Si grand est ton pouvoir transformant tout en rêve heureux

O nuit, ô laisse encore à la terre

Le calme enchantement de ton mystère

L'ombre qui t'escorte est si douce

Est-il une beauté aussi belle que le rêve ?

Est-il de vérité plus douce que l'espérance ?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrYXdCHs0UY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sREkrQY07Oc

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Foi, Musique, Sculpture | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : les choristes, nuit, rameau

mardi, 09 décembre 2014

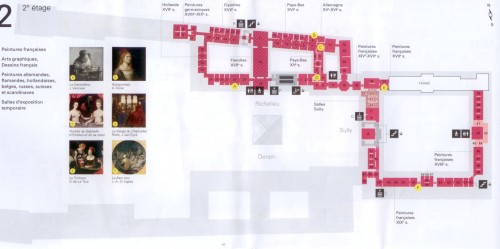

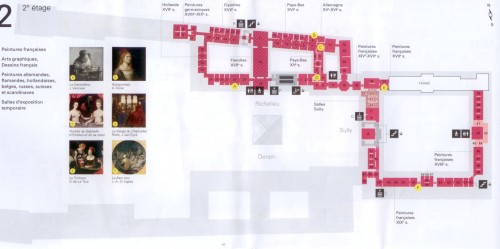

Où traîner ses guêtres pour faire plaisir à ses yeux ?

Réponse : Le deuxième étage du Louvre reste un endroit calme

en toutes saisons (suite)

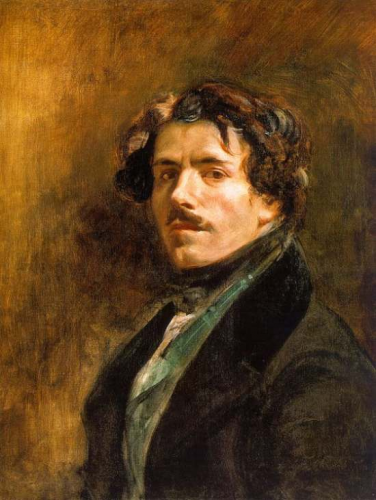

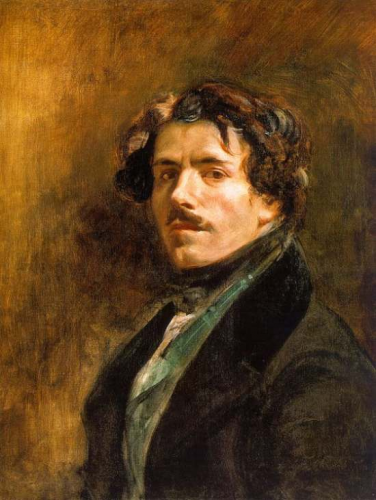

Léon Riesener, Eugène Delacroix Autoportrait, Eugène Delacroix

A gauche :

Léon Riesener, cousin d'Eugène Delacroix

A droite :

"Une physionomie farouche, étrange, exotique, presque inquiétante".

La description de Delacroix par Théophile Gautier est bien en accord avec ce

"portrait au gilet vert", le plus fameux des autoportraits de l'artiste.

Moine lisant, Camille Corot (1796-1875)

Cathédrale de Chartres, Camille Corot (1796-1875)

Les Sonneurs, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803-1860)

Ce tableau peint dans une veine rambranesque, fait allusion à une coutume de Brie, "le vin des morts" : à la Toussaint, le sonneur de cloches est remplacé par les garçons du village qui sonnent toute la nuit pour les âmes des défunts et reçoivent du vin en échange de leur peine.

> A consulter également :

> Et plus généralement :

http://fichtre.hautetfort.com/ou-trainer-ses-guetres.html

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Peinture, Sculpture | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : louvre

lundi, 08 décembre 2014

Où traîner ses guêtres pour faire plaisir à ses yeux ?

Réponse : Le deuxième étage du Louvre reste un endroit calme

en toutes saisons

Frédéric Chopin, Eugène Delacroix Autoportrait, Eugène Delacroix

A gauche :

Ce tableau, un fragment de la toile George Sand et Chopin, fut sans doute peint en 1838, année qui consacra la liaison de l'écrivain et du musicien, ami de l'artiste.

Restée inachevée, l’œuvre fut découpée entre 1863 et 1874.

Le portrait de George Sand est conservé à Copenhague.

A droite :

"Une physionomie farouche, étrange, exotique, presque inquiétante".

La description de Delacroix par Théophile Gautier est bien en accord avec ce

"portrait au gilet vert", le plus fameux des autoportraits de l'artiste.

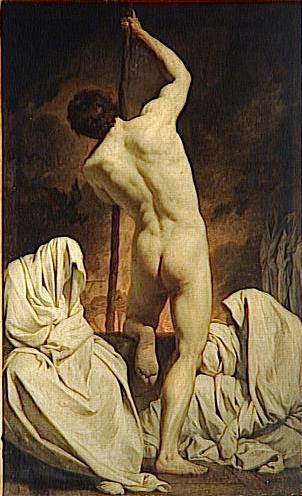

Caron passant les ombres, Pierre Subleyras (1699-1749)

La barque de Caron traverse le Styx pour conduire les âmes jusqu'aux enfers

La Baigneuse Valpinçon dite La grande baigneuse, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Connue sous le nom de Valpinçon, un de ses anciens possesseurs,

cette "Baigneuse" constitua en 1808 l'envoi de Rome à Paris de l'artiste,

alors pensionnaire de l'Académie de France.

Elle marque chez Ingres le point de départ d'une fameuse série de nus féminins.

Roméo et Juliette, Théodore Chasseriau (1819-1856)

Esquisse. Juliette étreint le corps inerte de Roméo dans la crypte funéraire. Sauf le détail de la coupe qui a contenu le breuvage mortel, l'artiste élimine tous les accessoires pour se concentrer sur l'effet pathétique de la scène.

Les deux carrosses, Claude Gillot (1673-1722)

> A consulter également :

> Et plus généralement :

http://fichtre.hautetfort.com/ou-trainer-ses-guetres.html

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Peinture, Sculpture | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : louvre, musée

dimanche, 23 novembre 2014

Considérations sur le corps - Nicholas Vujicic

Venus, Milo - Musée du Louvre

http://www.destination360.com/europe/france/paris/venus-de-milo

Nicholas James Vujicic, is an Australian preacher and motivational speaker born with Tetra-amelia syndrome, a rare disorder characterized by the absence of all four limbs. As a child, he struggled mentally and emotionally, as well as physically, but eventually came to terms with his disability and, at the age of seventeen, started his own non-profit organization, Life Without Limbs. Vujicic presents motivational speeches

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8jhcxOhIMAQ

07:05 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Portraits de personnalités, Réflexions, philosophie, Sculpture | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

mercredi, 22 octobre 2014

Etymologie - Romantique #3

Crédits photographiques Elie Mehdi

Extrait de Romancing the Market, Brown, Doherty & Clarke, 1998, Routledge :

p.2

Like many aesthetic movements, of course, romanticism only really makes sense in terms of what it is not. And the 'not' that romanticism is usually compared to is neoclassicism (allbeit the case for 'realism' is probably sttonger - see Travers 1998).

As the term implies, neoclassicism essentially involved the excavation, establishment, elaboration and enactment of aesthetic ideas derived from ancient Greek and Roman arbiters like Aristotle, Horace, Quintilian and Longinus (Abrams 1993; Barzun 1962). These authorities were assumed to have attained unequalled excellence in their respective spheres of endeavour and thus their writings were regarded as models to which all great art should aspire. Neoclassicism, then, was characterised by conformity, traditionalism, distrust of radical

p.3

innovation and an overwhelming emphasis upon the tried and tested. Its leading eighteenth-century exponents, such as Swift, Dryden, Pope and Goldsmith, stove for elegance, grace, decorum, propriety and adherence to, or refinement of, the 'rules' of the relevant genre. Innovation, admittedly, was by no means depreciated but the primary challenge was to display wit, ease, suavity, sophistication, skill and polish within existing, highly restricted conventions (in drama, the three unities of time, place and action, the closed couplet in poetry, etc.).

As Furst (1969: 15) observes, the authoritarianism of the neoclassical period largely stemmed from an unqualified belief in the powers of the mind, the intellect and, above all, reason. The scientific achievements of the Enlightenment fostered an assumption that all things were knowable and that this knowledge was attainable by means of rational investigation. Just as Newton had shown this to be the case in the physical world, so too the milieux of morals, politics, ethics and art could be systematically examined and their universal 'truths' uncovered, extracted and disseminated.

The adepts of neoclassicism thus attempted to establish the 'laws' of aesthetics, which if properly observed and carefully followed would result in a 'correct' composition, be it musical, literary, dramatic or whatever. 'The Rtist, like the scientist, was expected to operate by calculation, judgement and reason, for... the making of a book was considered a task like the making of a clock' (Furst 1969: 16).

The romantics, by contrast, championed innovation, creativity, iconoclasm, individuality and radical experimentation over traditionalism, refinement, rectitude and the seemly veneration of extant materials, forms, styles or genres (Butler 1981; Cranston 1994). They espoused spontaneity, informality, exuberance, elementalism, naturalism and aboriginal rusticity - as, for instance, in their use of vernacular language, their enthusiasm for 'lowly', 'impolite' or 'common' subjects, and, not least, their unqualified love of nature, landscape and the sheer élan vital of exitence. Conspicuously non-rational perspectives predicated upon visionary, mystical, supernatural, spiritual and otherworldly experiences came to prominence in the romantic period, as did a veritable catalogue of halt, lame and lonely wanderers, noble savages, innocent children, restless phantoms, pastoral panoramas, verdant vistas, sylvan glades, faery grottoes, crumbling ruins, gnarled oaks and, lest you think we've forgotten, golden daffodils. ALthough described with remarkable accuracy, compassion and power, it must be stressed that such 'external' phenomena primarily served to stimulate the inner feelings/reflections/emotions/introspections of the poet, author or creative artist.

Much of romanticism's legacy therefore comprises meditations or reveries on the creator's inner Self, though, as these people were often social misfits, nonconformists or malcontents, it is dominated by melancholic, anxiety-stricken, self-pitying expressions of the inner emotional turmoil of imaginative outsiders. Imagination, in short, coupled with an apocalyptic sense of out-with-the-old-and-in-with-the-new, was the cynosure of the romantics (Barzun 1944; Bowra 1961; Day 1996; Shaffer 1995). Romanticism is nothing less than an 'apocalypse of the imagination' (Bloom 1970a: 19).

p.10

[...] the romantic hero [...] is charismatic, dynamic, exciting, risk-taking, adventurous, outrageous, restless, roguish, swashbuckling, sexy. A bit Byronic perhaps, a tad Don Juanish and Manfred is manifestly its middle name [...]. Like Goethe's Werther, Chateaubriand's René and Musset's Octave, marketing constantly oscillates between profound, almost suicidal melancholy (e.g. the contemporary 'crisis' literature and the perennial complaint that no one takes the discipline seriously) and rampant, well-nigh certifiable megalomania (the broadening debate, periodic paroxysm of 'rediscovery', etc.). The romantic hero may be 'a multiple persona which drew upon images of the aristocrat, the dandy, the womaniser, the sociol and political outcast, and the rebel' (Travers 1998: 18), yet he is no less prone to 'lose a sense of perspective through constant self-observation, self-analysis and self-pity, so that he sinks deeper and deeper into the quagmire of his egocentricity' (Furst 1969: 98). Do they mean us ?

_ _ _

Contributors are Eric J. Arnould, Russel W. Belk, Stephen Brown, Bill Clarke, Anne Marie Doherty, Benoît Heilbrunn, Morris B. Holbrook, Christian Jantzen, Pauline Maclaran, Andrew McAuley, Per Ostergaard, Cele Otnes, Paul Power, Linda L. Price, Barbara B. Stern, Lorna Stevens, Craig J. Thompson, Robin Wensley

_ _ _

Abrams, M.H. (1993), A Glossary of Literary Terms, sixth edition, Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace.

Barzun, J. (1944), Romanticism and the Modern Ego, Boston: Little Brown.

Barzun, J. (1962), Classic, Romantic and Modern, London: William Pickering.

Bloom, H. (1970a), 'The internalization of quest romance', in H. Bloom, The Ringers in the Tower: Studies in Romantic Tradition, Chicago: Univeristy of Chicago Press, 12-35.

Bowra, M. (1961), The Romantic Imagination, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, M. (1981), Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries: English Literature and its Background 1760-1830, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cranston, M. (1994), The Romantic Movement, Oxford: Blackwell.

Day, A. (1996), Romanticism, London: Routledge.

Furst, L.R. (1969), Romanticism in Perspective: A Comparative Study of Aspects of the Romantic Povements in England, France and Germany, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Shaffer, E. (1995), 'Secular apocalypse: prophets and apocalyptics at the end of the eighteenth century', in M. Bull (ed.), Apocalypse Theory and the Ends of the World, Oxford: Blackwell, 137-58.

Travers, M. (1998), An Introduction to Modern European Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

_ _ _

Romancing the Market

Stephen Brown, Anne Marie Doherty, Bill Clarke

1998

Ed. Routledge

312 pages

http://www.amazon.fr/Romancing-Market-Stephen-Brown/dp/04...

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Les mots français, Photographie, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

mardi, 21 octobre 2014

Etymologie - Romantique #2

Crédits photographiques Elie Mehdi

Extrait de Romancing the Market, Brown, Doherty & Clarke, 1998, Routledge :

p.1

Two hundred years ago, a brace of young poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, scandalised polite society when they published the first edition of their poetic manifesto, Lyrical Ballads (Brett and Jones 1991). Inspired, in part, by the emancipatory euphoria that accompanied the unfurling of the French Revolution, and containing such never-to-be-forgotten (once-learnt-by-rote) classics as Tintern Abbey and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Lyrical Ballads ushered in a whole new era of Western culture, commonly known as romanticism or the romantic movement (Day 1996).

True, Wordsworth and Coleridge didn't actually employ the term 'romantic' (Furst 1971). The word and its cognates, what is more, were in widespread use prior to 1798 (Sanders, 1996). Indeed, the originality of Lyrical Ballads has also been called into question, as has the extent of the controversy surrounding its publication (Ashton 1996).Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that, thankgs in no small part to Wordsworth and Coleridge, the dog days of the eighteenth century witnessed a revolution in aesthetics, in sensibility, in thought. Not only did this represent, as Berlin (1991: 209) rightly records, 'the largest shift in European consciousness since the Reformation', but romanticism is still with us in the shape of our own great '-ism', our -ism in excelsis, the nulli secundus of -isms, postmodernism (Elam 1992; Livingston 1997 ; Readings and Schaber 1993).

p.2

The basic problem with -isms, of cours, is isn't (Brown 1995). That is to say, when it comes to -isms there isn't a single, satisfactory, all-encompassing, universally agreed definition, or even agreement on the fact that there isn't a single, satisfactory, all-encompassing, universally agreed definition of the -ism in question.

Whether it be realism, relativism, conservatism, liberalism, idealism, empiricism, communism, capitalism, fscism, feminism, gnosticism, aestheticism, asceticism, athleticism, mysticism, mesmerism, masochism, modernism, marxism, malapropism or any othe '-ism' that those mad for macaronicism, liable to lexiphanicism or smitten by sesquipedalianism are inclined to conjugate, the only thing that everyone knows for certain is that there is no certainty about the thing everyone 'knows". The ism isn't.

The same is true for romanticism, a subject which has been subject to all manner of competing definitions ranging from Rousseau's 'return to nature", though Pater's 'the addition of strangeness to beauty', to Phelps's 'sentimental melancholy' (see Furst 1971). How, for that matter, can we possibly forget Goethe's contention that 'romanticism is disease' (young Werther has a lot to be sorrowful for), Ker's suggestion that it represents 'the fairy way of writing' (not in this neck of the woods, buster !), and Fairchild's cryptic confabulation that romanticism comprises 'a desire to find the infinite within the finite, to effect a synthesis of the real and the unreal, the expression in art of what in theology would be called pantheistic enthusiasm' (keep taking the tables, sunshine, or the laudanum at least) ?

Aptly described as 'baffingly vague and used in an appallingly large number of different ways in different contexts' (Gray 1992: 251), romanticism is degined in The Oxford Companion to English Literature as :

A literary movement, and profound shift in sensibility, which took place in Britain and throughout Europe... Intellectually it marked a violent reaction to the Enlightenment. Politically it was inspired by the revolutions in America and France... Emotionnaly it expressed an extreme assertion of the self and the value of individual experience together with the sense of the infinite and transcendental... The stylistic keynote of romanticism is intensity, and its watchword is 'imagination".

(Drabble 1995: 853)

_ _ _

Contributors are Eric J. Arnould, Russel W. Belk, Stephen Brown, Bill Clarke, Anne Marie Doherty, Benoît Heilbrunn, Morris B. Holbrook, Christian Jantzen, Pauline Maclaran, Andrew McAuley, Per Ostergaard, Cele Otnes, Paul Power, Linda L. Price, Barbara B. Stern, Lorna Stevens, Craig J. Thompson, Robin Wensley

_ _ _

Ashton, R. (1996), The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Oxford: Blackwell.

Berlin, I. (1991), 'The apotheosis of the romantic will: the revolt against the myth of an ideal world', in I. Berlin (ed.), The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas, London: Collins, 207-37.

Brett, R.L. and Jones, A.R. (1991), 'Introduction', in W. Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, London: Routledge, ixi-liv.

Brown, S. (1995), Postmoderne Marketing, London: Routledge.

Day, A. (1996), Romanticism, London: Routledge.

Drabble, M. (ed.) (1995), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elam, D. (1992), Romancing the Postmodern, London: Routeledge.

Furst, L.R. (1971), Romanticism, London : Methuen.

Gray, M. (1992), A Dictionary of Literary Terms, Harlow: Longman.

Livingston, I. (1997), Arrow of Chaos : Romanticism and Postmodernity, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Readings, B. and Schaber, B. (eds) (1993), Postmodernism Acreoss the Ages: Essays for a Postmodernity That Wasn't Born Yesterday, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Sanders, A. (1996), A Short Oxford History of English Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_ _ _

Romancing the Market

Stephen Brown, Anne Marie Doherty, Bill Clarke

1998

Ed. Routledge

312 pages

http://www.amazon.fr/Romancing-Market-Stephen-Brown/dp/04...

07:00 Publié dans Beaux-Arts, Les mots français, Photographie, Sculpture, Thèse | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)